You can control PCOS with diet, lose weight and fall pregnant by making simple lifestyle changes that improve your insulin sensitivity and lower your androgen levels. Keep reading to learn more.

Do weight loss and pregnancy seem like an impossible feat?

If you live with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the idea of maintaining a healthy weight or being surrounded by children squealing with delight can feel out-of-reach.

But no matter how severe your PCOS, making some simple dietary changes can facilitate weight loss and dramatically improve your chances of conceiving naturally or otherwise.

But first, what is PCOS?

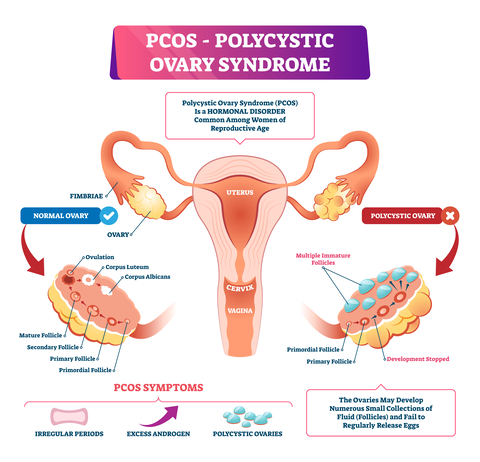

PCOS is a common, heritable endocrine disorder that affects women of reproductive age throughout their lifetime.

It causes your body to produce excess male hormones (androgens), including testosterone and androstenedione and stops your ovaries from functioning correctly.

Your ovaries also contain many under-developed follicles or ‘cysts’. And although unnecessary for diagnosis, you may have insulin resistance.

PCOS affects around 6-9% of women globally and at similar rates across all ethnicities.

Scientists don’t know what causes PCOS, but current evidence suggests that genetic and environmental factors, such as diet and lifestyle, play a role.

Other studies suggest that PCOS may start in a baby during pregnancy if its mother has hypertension, diabetes or smokes. These factors, environmental chemicals, certain drugs and diet may stunt the baby’s growth and permanently reprogramme its metabolic functioning, increasing its risk of developing PCOS later in life.

You may have PCOS if you experience these symptoms.

Clinicians diagnose PCOS by excluding other conditions with similar characteristics.

Some of these conditions include adrenal and ovarian cancers, Cushing syndrome, non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hyperprolactinaemia, thyroid dysfunction and premature ovarian failure.

If none of these conditions is present and you have two or more of the following features (excluding acne), your clinician will diagnose PCOS.

1 | Period abnormalities: This includes irregular periods (affects 85-90% of women with PCOS), no periods (affects 30-40% of women with PCOS) or prolonged periods with irregular bleeding. However, 30% of women with PCOS have regular periods.

Women with PCOS also have high levels of luteinising hormone.

2 | Abnormal hair growth (hirsutism): Excessive hair growth on the face (upper lip and chin) and around the body (chest, back, abdomen, arms and thighs) affects up to 70% of women with PCOS.

Hirsutism is a consequence of excessive androgen (hyperandrogenism) release.

3 | Acne: Severe acne can be a sign of hyperandrogenism, but it is not a reliable PCOS sign. Approximately 15-30% of women with PCOS have acne.

4 | Infertility: Up to 40% of women with PCOS are infertile. Infertility occurs because the follicles don’t grow to maturity. Mature follicles are usually 17-25mm in diameter, but in PCOS, follicles only reach a 4-8mm diameter.

Because none of these follicles grows to maturity, ovulation doesn’t occur (anovulation).

5 | Polycystic ovaries: The ovaries are polycystic if they contain twelve or more follicles measuring 2-9mm in diameter and an ovarian volume greater than 10cm3.

PCOS affects women differently

It is mild in some women and severe in others. Clinicians classify PCOS into four types based on severity.

- Classic PCOS is the most severe. Women don’t ovulate, produce excess androgens and have polycystic ovaries.

- Classic non-polycystic ovary PCOS is the next most severe. Women don’t ovulate, produce excess androgens but have normal ovaries.

- Non-classic ovulatory PCOS is less severe. Women have regular menstrual cycles, but they produce excess androgens and have polycystic ovaries.

- Non-classic mild or normal-androgenic PCOS is the least severe. Women don’t ovulate, have polycystic ovaries, but they produce androgens at a standard rate.

| Table 1: Types of polycystic ovary syndrome according to the severity | ||||

| Type | Classic (Frank) | Classic non-polycystic ovary | Non-classic ovulatory | Non-classic mild or normal androgenic |

| Features | No ovulation Excess androgens Polycystic ovaries | No ovulation Excess androgens Normal ovaries | Normal periods Excess androgens Polycystic ovaries | No ovulation Normal androgens Polycystic ovaries |

| Severity | ++++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| ++++: most severe; +++: severe; ++: less severe; +; least severe. |

PCOS increases your risk of other chronic conditions.

1 | Obesity: Obesity is one of the most critical features of PCOS, affecting up to 80% of women. Women with PCOs have excess fat around their organs (visceral fat) and under their skin (subcutaneous fat) due to excessive androgen production.

Fat accumulates mainly around the abdominal region, increasing the risk of metabolic syndrome.

Women with PCOS have high low-density lipoprotein (LDL or ‘bad cholesterol’) =and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL or ‘good cholesterol’) levels, which increases their risk of developing atherosclerosis (fat build-up in the arteries).

This lipid profile is present both in lean and obese women with PCOS.

2 | Insulin resistance: Insulin is the hormone your pancreas releases to maintain normal glucose levels. It enables your body to use glucose as fuel or store it as body fat and regulates fat and protein metabolism. Insulin resistance occurs when insulin can’t do its job correctly.

Your pancreas may compensate by producing more insulin. However, the extra insulin doesn’t normalise your blood glucose levels, and your insulin levels remain higher than usual. When this happens, you have hyperinsulinemia.

Hyperinsulinemia affects 85% of women with PCOS, including 95% of obese and 65% of lean women.

It increases luteinising hormone levels, stops your follicles from growing to maturity and prevents ovulation. Hyperinsulinemia also suppresses sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and encourages your ovaries to produce androgens.

3 | Type II Diabetes: About 20% of women with PCOS develop type II diabetes (TIID), a rate that is significantly higher than in women without PCOS. The increased risk of TIID in women with PCOS is due to obesity and insulin resistance, but a family history of TIID further increases this risk.

It is worth noting that TIID can occur in lean women with PCOS, even without a family history of TIID, mainly due to insulin resistance.

4 | Infertility: Infertility is ten times more common in women with PCOS than in those without it. Women with PCOS may be less fertile because their ovaries function incorrectly. Research shows that up to 50% of women with PCOS experience primary infertility and 25% secondary infertility.

Women who successfully conceive have a higher risk of developing gestational diabetes, hypertension and pre-eclampsia than women without it. They also have a three-fold higher risk of miscarriage and having underweight babies than women without PCOS.

5 | Endometrial cancer: Women with PCOS have a three-fold higher risk of developing endometrial cancer than women without, likely due to continuous oestrogen exposure. Despite this, the prognosis is good.

6 | Mood disorders: Women with PCOS have a higher risk of depression (35% vs 10.7%), bipolar disorder (27% vs 0.5%-2%) and binge eating disorder (12.6% vs 1.9%) than women without PCOS.

Scientists agree that diet is the first line of therapy for PCOS. When diet is adequate, women lose weight, reduce androgen levels, normalise menstrual cycles, and in some cases fall pregnant spontaneously.

So, what diet is best for PCOS?

Scientists have investigated several dietary patterns, including low carbohydrate, ketogenic, anti-inflammatory, low GI and high protein, to determine the best diet for PCOS.

While all of these diets facilitate weight loss, some are more effective to lower testosterone, induce ovulation and improve insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles.

In a 12-week study of 28 obese women with PCOS, a high-protein, low carbohydrate diet was slightly more effective at improving HDL-C concentrations and encouraging conception than a low protein-high carbohydrate diet. However, both diets were equally effective to lower insulin resistance and testosterone levels, weight loss, more regular cycles and pregnancies.

Another study of 60 overweight and obese women with PCOS showed that a high protein, low GI weight loss diet increased insulin sensitivity and lowered inflammatory proteins more effectively than a standard protein weight loss diet.

The anti-inflammatory diet, a plant-rich diet containing minimal meat and chicken with at least two portions of fish per week, has shown the best improvements in reproductive function. After 12 weeks on a weight loss anti-inflammatory diet, 63% of women with PCOS regained regular cycles and 12% conceived naturally.

Unlike other studies, a low-starch (<20% of calorie intake) low-dairy diet successfully reduced free and total testosterone and hair growth in women with PCOS. A ketogenic diet also induces weight loss, significantly increases insulin sensitivity, lowers triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL-C. It also improves HDL-C, SHBG and hirsutism.

Few studies have compared these dietary patterns against one another to determine the most effective approach. And as current studies involve few participants, it is challenging to draw finite conclusions.

We don’t know which diet is best for PCOS right now.

But we know that as long as obese women with PCOS achieve weight loss through diet and exercise, their insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles improve, testosterone levels reduce, cycles regularise, and pregnancy chances improve.

In essence, it doesn’t matter which of these diets you follow as long as it is:

- rich in whole foods

- low in saturated fat

- provides adequate nutrients

- sustainable and

- promotes weight loss

Use these evidence-based dietary strategies to lose weight and fall pregnant

Reducing insulin resistance (and improving insulin sensitivity) is the key to PCOS control, weight loss and pregnancy. The specific dietary changes you can implement to improve your insulin sensitivity include the following:

1 | Add more ‘bulk’ to your diet: Fibre is the portion of plant foods your body can’t digest. It regulates your blood glucose by slowing glucose absorption and increases your insulin sensitivity.

It also helps you feel full and reduces the number of calories you eat. High fibre intakes are linked to weight loss and improved insulin sensitivity in women with PCOS.

Aim to eat at least 30g of fibre daily.

How to: Increase your fibre intake by swapping refined foods with whole, unprocessed foods. E.g., eat brown, red or black rice in place of white rice, and eat wholewheat pasta instead of white pasta.

Eat whole fruit instead of drinking smoothies and juices and increase the number of fruits and vegetables you eat.

Read this post for more tips on how to boost your fibre intake.

2 | Eat more anti-inflammatory fats: Chronic low-grade inflammation is a component of many obesity-related disorders, and PCOS is no exception. Omega-3 fatty acids are proven anti-inflammatory compounds that can improve inflammation in PCOS.

Previous studies show that omega-3 supplements reduce LH, insulin, and testosterone levels and increase insulin sensitivity in women with PCOS. And they promote weight loss, as evidenced by lower BMI and waist circumference measurements in these women.

How to: Cold-water fish such as salmon, mackerel, herring and sardines are excellent omega-3 sources. Eat two 120g portions at least twice a week. Fatty fish are also good sources of vitamin D, which is often lacking in women with PCOS.

Walnuts, chia and flaxseeds are also good sources of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), but not the beneficial eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) omega-3 present in fish.

Your body converts ALA to EPA and DHA, albeit in minimal quantities (~10% conversion rate). That said, a recent study shows that flaxseed oil lowers inflammatory markers in women with PCOS.

3 | Limit or eliminate ‘fast’ carbs: Whole, unprocessed carbohydrates such as brown rice, corn, millet, potatoes, sweet potatoes, beans, lentils, peas, plantains, and yams are ‘slow carbs’ that are rich in dietary fibre.

They are slow carbs because they slowly raise your blood sugar and insulin levels, unlike white rice, flour, and bread that spike your glucose and insulin levels.

A low GI diet improves insulin resistance, reduces testosterone, promotes weight loss and induces ovulation with spontaneous pregnancy in women with PCOS. A high-GI diet, in contrast, worsens insulin resistance and prevents weight loss and pregnancy.

How to: Eat a whole-foods diet by replacing all fast, high-GI carbs (e.g., sugar, agave syrup, white flour, sweets, cakes, pastries) with whole, natural foods such as potatoes, brown rice, yams, plantains, beans, nuts and seeds. And eat them in proportions that promote weight loss.

You can achieve weight loss by filling half your plate with leafy green vegetables such as greens, broccoli, efo riro, and okra and filling the other half of your plate with a combination of starchy vegetables like potatoes or whole grains like brown rice and proteins like beans, lentils, fish or lean poultry.

4 | Improve your cardiovascular health and build strength: Exercise improves insulin sensitivity, lowers testosterone, promotes weight loss and lowers inflammation in women with PCOS. Women with PCOS who exercise regularly also improve their acne and achieve more regular menstrual cycles.

What to do: Go for a brisk walk, run or jog for 30 minutes at least five days a week. Otherwise, do other activities you enjoy (e.g., tennis, hockey) that increase your heart rate.

Don’t forget to include strength/resistance-training exercises at least twice a week to maintain your muscle mass. Regular strength-training increases your muscle mass and increases your resting metabolic rate, and may help you burn fat faster.

If you hate the gym or prefer not to exercise outdoors, no problem! You can workout in the comfort of your home – YouTube has a plethora of free exercise programmes for all fitness levels.

5 | Take a vitamin D supplement: As well as keeping your bones and teeth healthy, Vitamin D helps your follicles develop and maintains normal insulin function. Studies show that women with PCOS have lower vitamin D levels than women without PCOS, potentially making PCOS symptoms worse.

That said, vitamin D’s benefits in women with PCOS are inconsistent. In some studies, vitamin D supplements lower total testosterone, LDL-C and total cholesterol and improve insulin sensitivity. But, in others, these benefits are absent.

Although the possible benefits of vitamin D supplements in women with PCOS are inconclusive, vitamin D is necessary for immunity, bone and teeth health.

So, it’s still worth improving your vitamin D intake, particularly if you’re deficient.

What to do: Fatty fish and UV-treated mushrooms are excellent sources of vitamin D. Eat mushrooms as often as you wish and aim to eat at least two portions of fatty fish per week.

I also recommend taking a 10µg vitamin D supplement daily.

6 | Eat balanced meals: Fill half your plate with colourful vegetables, a quarter with whole, starchy carbohydrates and the last quarter with quality proteins. Include small to moderate quantities of quality fat such as avocado, nuts and seeds.

You should also try to include quality proteins at every meal, including breakfast.

And there you have it, the diet and lifestyle changes you should implement to control your PCOS, lose weight and fall pregnant.

Remember, weight loss, no matter how small, will improve your insulin sensitivity and likely regularise your cycles to improve your chances of falling pregnant.

Eat a healthy diet, exercise regularly, stress less, be patient, and let your new healthy lifestyle work its magic.

Don’t forget to come back and leave your success story when it happens. I can’t wait to celebrate with you!

REFERENCES

- Sirmans, S.M., and Pate, K.A. (2014) Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clinical Epidemiology, 6, 1–13.

- Wolf, W.M., Wattick, R.A., Kinkade, O.N., and Olfert, M.D. (2018) Geographical prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome as determined by region and race/ethnicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 2589; doi:10.3390/ijerph15112589.

- Escobar-Morreale, H.F. (2018) Polycystic ovary syndrome: definition, aetiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 270, 14, 270–284.

- El Hayek, S., Bitar, L., Hamdar, L.H., Mirza, F.G., and Daoud, G. (2016) Polycystic ovarian syndrome: An updated overview. Frontiers in Physiology, 7, 14, doi:10.3389/fphys.2016.00124.

- Richmond, J.R., Deshpande, N., Lyall, H., Yates, R.W.S., and Fleming, R. (2005) Follicular diameters in conception cycles with and without multiple pregnancy after stimulated ovulation induction. Human Reproduction, 20, 3, 756–760.

- Lee, T.T., and Rausch, M.E. (2012) Polycystic ovarian syndrome: Role of imaging in diagnosis. RadioGraphics, 32(6), https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.326125503.

- Wilcox, G. (2005). Insulin and insulin resistance. Clinical Biochemist Reviews, 26(2), 19–39.

- Shanik, M.H., Xu, Y., Skrha, J., Dankner, R., Zick, Y., Roth, J. (2008) Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care, 31(Suppl 2), S262–8.

- Thomas, D.D., Corkey, B.E., Istfan, N.W., and Apovian, C.M. (2019) Hyperinsulinemia: An early indicator of metabolic dysfunction. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 3(9), 1727–1747.

- Katulski, K., Czyzyk, A., Podfigurna-Stopa, A., Genazzani, A.R., Meczekalski, B. (2015) Pregnancy complications in polycystic ovary syndrome patients. Gynaecological Endocrinology, 31, 87–91.

- Moran, L.J., Noakes, M., Clifton, M., Tomlinson, L., and Norman, R.J. (2003). Dietary composition in restoring reproductive and metabolic physiology in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 88(2), 812–819.

- Mehrabani, H.H., Salehpour, S., Amiri, Z., Farahani, S.J., Meyer, B.J., and Tahbaz, F. (2012) Beneficial effects of a high-protein, low-glycemic-load hypocaloric diet in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomised controlled intervention study. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 31(2), 117–25.

- Panidis, D., Tziomalos, K., Papadakis, E., Vosnakis, C., Chatzis, P and Katsikis, I. (2013) Lifestyle intervention and anti-obesity therapies in the polycystic ovary syndrome: impact on metabolism and fertility. Endocrine, 44, 583–590.

- Phy, J.L, Pohlmeier, A.M., Cooper, J.A., Watkins, P., Spallholz, J., Harris, K.S., Berenson, A.B., and Boylan, M. (2015) Low starch/low dairy diet results in successful treatment of obesity and co-morbidities linked to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Journal of Obesity and Weight Loss Therapy, 5(2): doi:10.4172/3165-7904.1000259.

- Moran, L.J., Pasquali, R., Teede, H.J., Hoeger, K.M., Norman, R.J. (2009) Treatment of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: a position statement of the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Fertility and Sterility, 92, 1966–1982.

- Paoli, A., Mancin, L., Giacona, M.C., Biano, A., and Caprio, M. (2020) Effects of a ketogenic diet in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Translational Medicine, 18: 104.

- Mavropoulous, J.C., Yancy, W.S., Hepburn, J., and Westman, E.C. (2005) The effects of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on the polycystic ovary syndrome: A pilot study. Nutrition and Metabolism, 2: 35

- Nybacka, A., Hellstrom, P., and Hirschberg, A.L. (2017) Increased fibre and reduced trans fatty acid intake are primary predictors of metabolic improvement in overweight polycystic ovary syndrome – substudy of randomised trial between diet, exercise and diet plus exercise for weight control.

- Farshchi, H., Rane, A., Love, A., and Kennedy, R.L. (2007) Diet and nutrition in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): Pointers for nutritional management. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27(8), 762-773.

- Shahdadian, F., Ghiasvand, R., Abbasi, B., Feizi, A., Saneei, P., and Shahshahan, Z. (2019) Association between major dietary patterns and polycystic ovary syndrome: evidence from a case-control study. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism, 44(1), 52–58.

- Porchia, L., Hernandez-Garcia, S.C., Gonzalez-Mejia, M.E., and Lopez-Bayghen, E. (2020) Diets with lower carbohydrate concentrations improve insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 248, 110–117.

- Salama, A.A., Amine, E.K., Salem, H.A. and Abd El Fattah, N.K., (2015) Anti-inflammatory dietary combo in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 7, 310–6.

- Mirmasoumi, G., Fazilati, M., Foroozanfard, F., Vahedpoor, Z., Mahmoodi, S., Taghizade, M., Esfeh, N.K., Mohseni, M., Karbassizadeh, H., and Asemi, Z. (2018) The effects of flaxseed oil omega-3 fatty acids supplementation on metabolic status of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Experimental Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 126(4), 222–228.

- Oner, G., Muderris, II. (2013) Efficacy of omega-3 in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 33, 289–291.

- Ebrahimi, F.A., Samimi, M., Foroozanfard, F., Jamilian, M., Akbari, H., Rahmani, E., et al. (2017). The effects of omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin E co-supplementation on indices of insulin resistance and hormonal parameters in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Experimental Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes, 125, 353–359.

- Salek, M., Clark, C.C.T., Taghizadeh, M., and Jafarnejad, S. (2019) N-3 fatty acids as preventive and therapeutic agents in attenuating PCOS complications. EXCLI Journal, 18, 558–575.

- Swanson, D., Block, R., and Mousa, S.A. (2012) Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: Health benefits throughout life. Advances in Nutrition, 3(1), 1–7.

- Hernandez-Sordia, L.H., Rodriguez, P.A., Rodriguez, D.S., Guzman, S.T., Zenteno, E.S.S., Gonzalez, G.G., and Patino, R.I. (2016) Effects of a low glycemic diet in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome and anovulation – randomised controlled trial. Clinical Experimental Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 43(4), 555–559.

- Shishehgar, F., Mirmiran, P., Rahmati, M., Tohidi, M., Tehrani, F.R. (2019) Does a restricted-energy low glycaemic index diet have a different effect on overweight women with or without polycystic ovary syndrome? BMC Endocrinology Disorders, 19(1), 93.

- Marsh, K and Brand-Miller, J. (2005) The optimal diet for women with polycystic ovary syndrome? British Journal of Nutrition, 94(2), 154–165.

- Fica, S., Albu, A., Constantin, M., and Dobri, G.A. (2008) Insulin resistance and fertility in polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Medicine and Life, 1(4), 415–422.

- Kareem, H.S., Khalil, N.K.M., Badr, N.M.H., El-Shamy, F. (2014) The effect of exercise on insulin resistance in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. The Egyptian Journal of Internal Medicine, 26(3), 110–115.

- Aristizabal, J.C., Freidenreich, D.J., Volk, B.M., Kupchak, B.R., Saenz, C., Maresh, C.M., Kraemer, W.J., Volek., J.S. (2015) Effect of resistance training on resting metabolic rate and its estimation by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry metabolic map. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(7), 831–6.

- Lin, M-W., and Wu, M-H. (2015) The role of vitamin D in polycystic ovary syndrome. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 142(3), 238-240.

- Menichini, D., and Facchinetti, F. (2019) Effects of vitamin D supplementation in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a review. Gynaecological Endocrinology, doi:10.1080/09513590.2019.1625881.

- Trummer, C., Schwetz, V., Kollmann, M., Wolfler, M., Munzker, J., Pieber, T.R., Pilz, S., Heijboer, A.C., Obermayer-Pietsch, B., and Lerchbaum, E. (2019) Effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic and endocrine parameters in PCOS: a randomised-controlled trial. European Journal of Nutrition, 58(5), 2019–2028.

- Miao, C.Y., Fang, X-J., Chen, Y., and Zhang, Q. (2020) Effect of vitamin D supplementation on polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 19(4), 2641–2649.